When residents walked into the Ivanhoe Centre for the Whitestone 1 consultation, they were met with tables covered in large, colourful maps showing neat green blocks of solar panels and tidy boundaries. At first glance, it looked organised, controlled, and almost harmless.

But there was another map — one hidden away in folders, only shown if you knew to ask. And the difference between the two couldn’t be more striking.

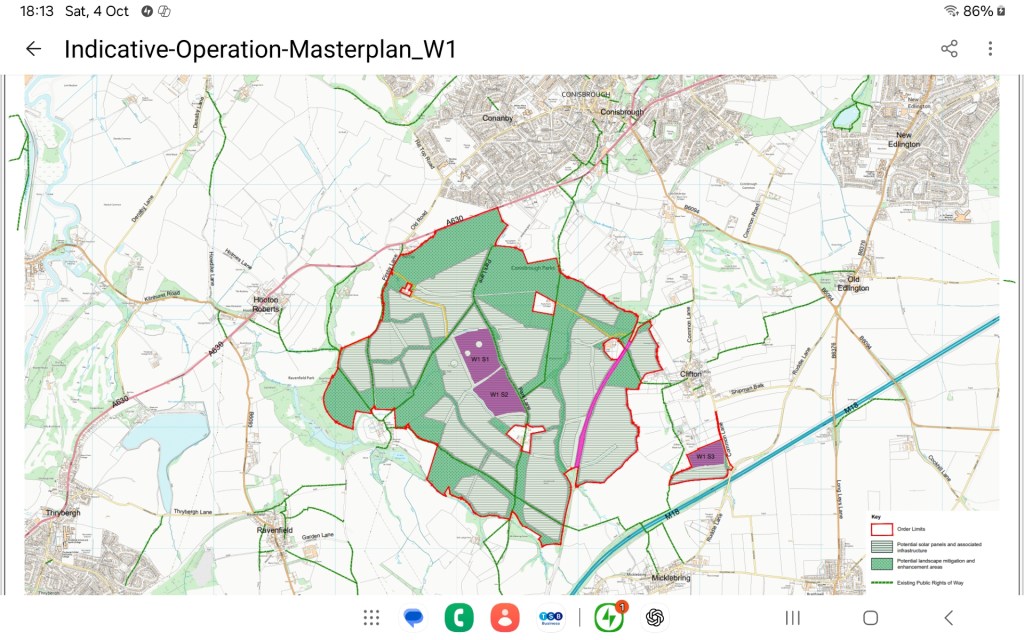

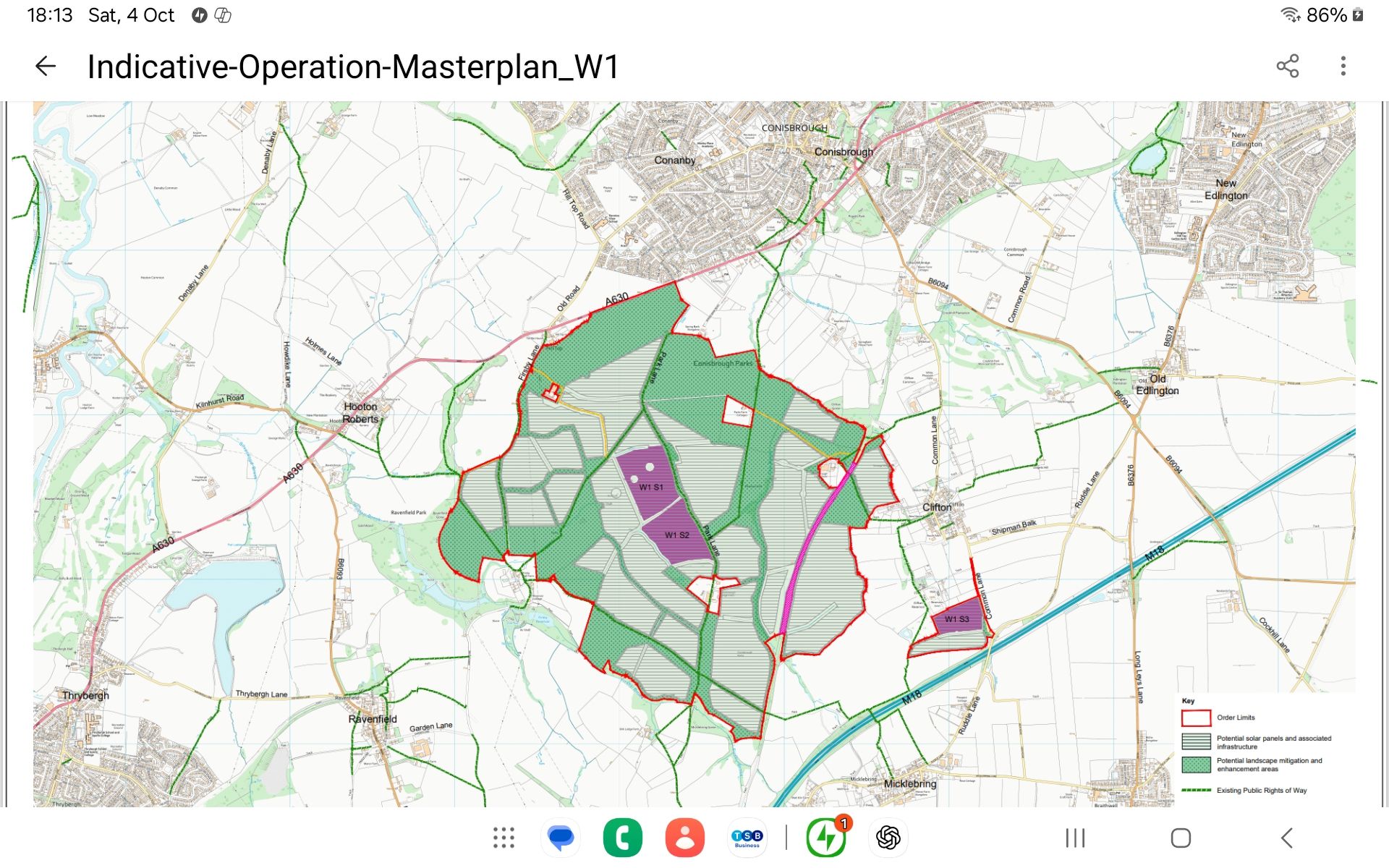

The Map They Wanted You to See

On the tables was the Indicative Operation Masterplan. It looked reassuringly clean: fields shaded in soft green, with faint outlines marking proposed panel areas. Substations and battery storage sites were neatly symbolised, public rights of way (PROWs) appeared untouched, and the countryside still seemed largely intact.This was the map used to sell the project’s image — a “low impact,” “green energy” development that could somehow sit quietly on farmland without much fuss.But it was a carefully edited illusion.

The Map They Hid Away

Inside the consultation folders, in much smaller scale and harder to read, was the Indicative Construction Masterplan — the real story.

This map showed what the public was never meant to focus on:

Cable route corridors (CR1a–CR1d) slicing through farmland.

Construction compounds and internal access tracks crisscrossing fields.

Vehicle crossing points and hedgerow breaks for trenching and heavy plant access.

Substation and BESS sites sprawling near existing brooks and drainage lines.In this version, the scale of the disruption became obvious.

Hedgerows marked for removal.

Long-established bridleways and footpaths missing or redirected.

Access routes cutting through productive farmland and sensitive habitats.

Yet none of this was displayed on the large public maps — and few residents even realised the hidden version existed until they asked to see it.

The Missing Details

No clear answers were given on:

How many hedgerows would be removed or replaced.

Which PROWs and horse trails would be closed or diverted.

The exact locations of construction compounds, or their proximity to flood-prone fields.

How BESS fire access or emergency safety measures would be managed.

The drainage consequences for nearby brooks and low-lying farmland already vulnerable to flooding.

For a project of this magnitude, those details are not optional — they are essential. Without them, the community cannot make an informed judgment.

The Illusion of Transparency

By displaying the simplified operation map and hiding the disruptive construction map, developers created an illusion of transparency.

They could claim they had “shown the plans,” but the reality was a PR exercise designed to calm resistance, not to inform decision-making.

The Planning Inspectorate has already criticised Whitestone 1 for being “too vague” and missing key data, and the Conisbrough event proved that criticism entirely correct.

When the truth sits in a folder rather than on the wall, it’s not consultation — it’s concealment.

Why It Matters

The people of Clifton, Ravenfield, and Firsby are being asked to accept an industrial-scale development that will tear through their countryside, remove hedgerows, threaten local flood defences, and disrupt long-used paths and bridleways.

Showing the public a polished, cropped version of reality is not engagement — it’s manipulation.As one resident said, standing over the maps that day: “They’ve shown us the pretty picture — not the damage underneath.”

The Message from Conisbrough

This is why trust in the process has broken down. Communities don’t object to being consulted — they object to being deceived.

If Whitestone’s developers truly believed in transparency, they would have put both maps side by side on those tables and invited residents to see the full picture.Instead, they chose presentation over honesty. And that choice has consequences.

Conisbrough has seen through the gloss — and it won’t be forgotten.

Leave a comment