Introduction

For years, the British public has been told that solar energy is cheap, clean, and the key to our energy future. Successive governments, the Climate Change Committee (CCC), and environmental campaigners have promoted vast ground-mounted solar farms as the answer to decarbonisation. Yet when we look past the slogans and examine what is actually happening on our national grid, a very different picture emerges.

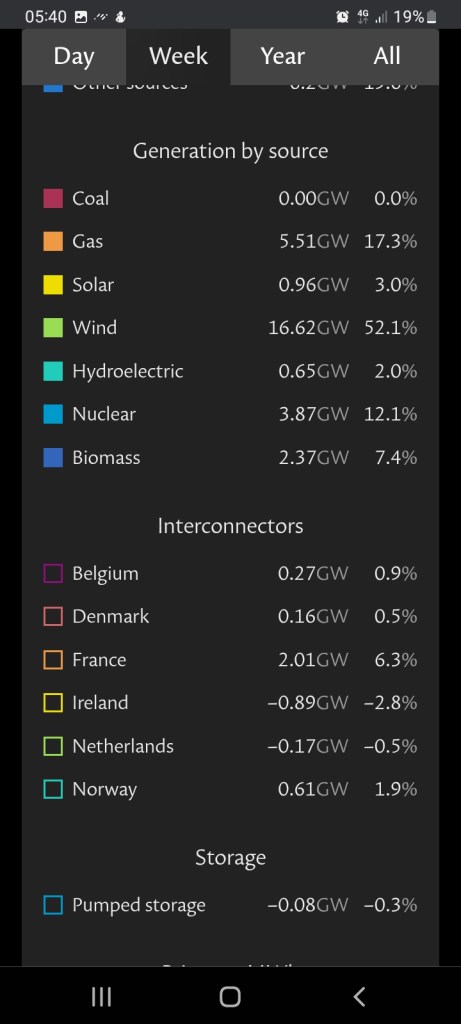

My screenshots from the National Grid data platform show, in plain numbers, that solar contributes almost nothing for large parts of the day and year. It is intermittent, inefficient, and dependent on expensive backup systems that drive costs up, not down. The data reveal what engineers have warned for decades — that large-scale solar in the UK was always a political fantasy, not a technical solution.

What the Data Actually Show

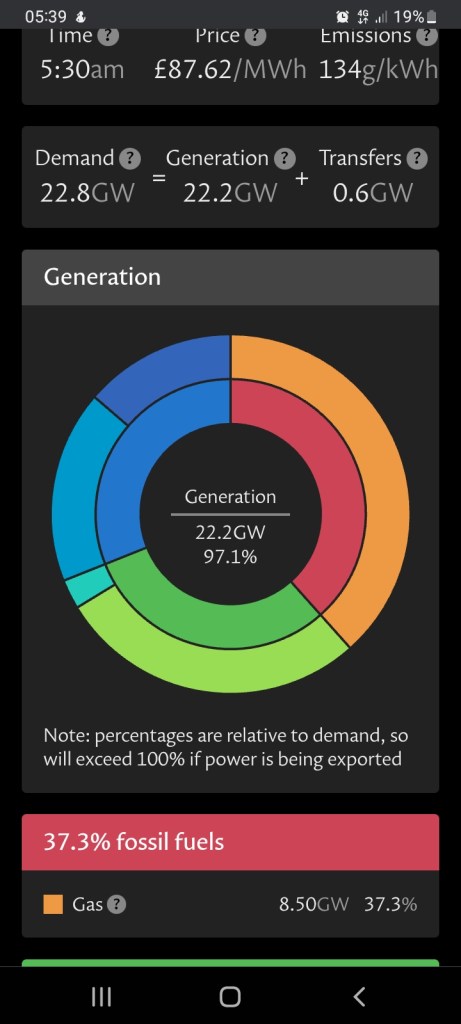

Screenshot 1 – 5:30 am generation mix.

My screenshots show the situation at 5:30 a.m. when national demand was 22.8 GW. Solar produced 0.00 GW — zero. Fossil fuels (mainly gas) supplied 8.5 GW, wind 6.17 GW, nuclear 3.84 GW, and biomass 3.03 GW. In other words, 100 % of Britain’s power at that hour came from sources other than solar.This pattern repeats every night of the year. Solar produces nothing in darkness, and very little in winter months when the sun is low and cloud cover high. The UK’s latitude, short winter days, and frequent overcast conditions make it physically impossible for solar to provide reliable baseload power.

Comparing Daily, Weekly, and Yearly Output.

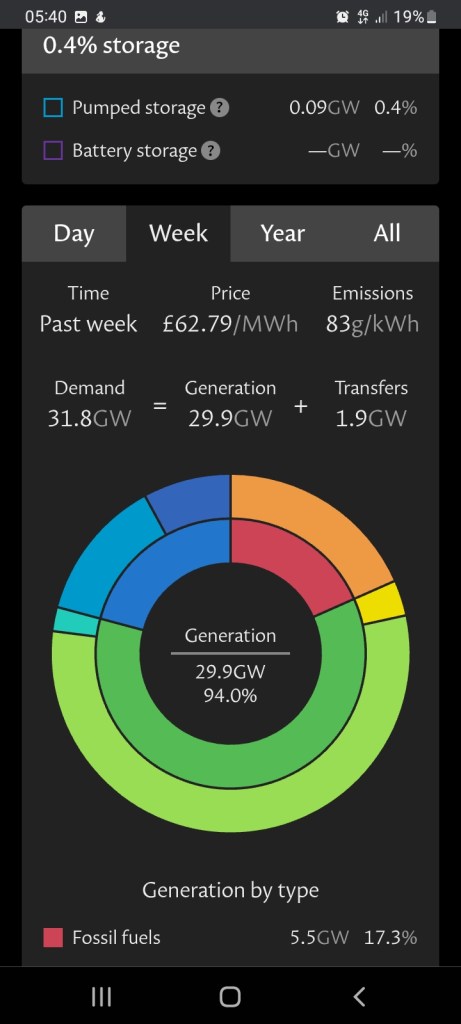

Screenshot 2 – daily generation by type.My screenshots show that even when averaged over a whole week, solar still plays only a minor role. Over the past week, renewables provided around 65 % of total power, but wind did almost all of the work. Solar contributed just 3 % of generation, dwarfed by gas at 17 % and wind at over 50 %

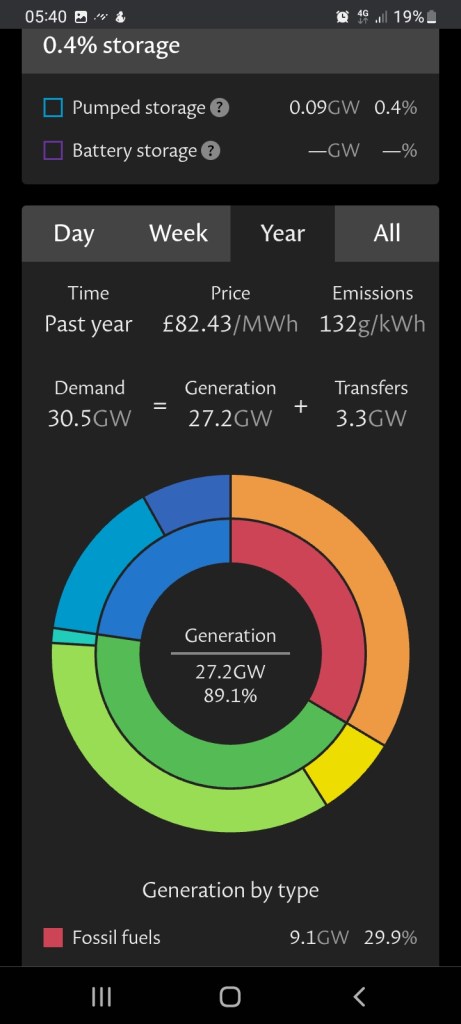

Screenshot 3 – yearly generation by type

Looking at the yearly averages, the picture remains almost unchanged. Solar’s share across the year was around 6 – 7 %, despite thousands of acres of farmland now being converted into solar arrays. Gas supplied about 30 %, wind 31 %, nuclear 13 %, and biomass 7 %.These numbers show that, even after more than a decade of subsidies, feed-in tariffs, and planning relaxations, solar still makes up less than one-tenth of our total generation — and almost none of it during peak demand hours.

The Physics Problem:

Britain Is Not California or Spain.Solar energy depends on the intensity of sunlight, known as insolation. In southern Europe or North Africa, annual solar radiation exceeds 2,000 kWh/m². In the UK it rarely reaches 1,000 kWh/m², and in December it falls to a fraction of that.The result is a deep seasonal imbalance: generation collapses in winter when heating and lighting demand are highest. My screenshots show this mismatch clearly -winter weeks where solar’s contribution is effectively nil, even while demand remains above 30 GW.No government target or Climate Change Committee directive can alter the tilt of the Earth. Britain’s climate simply doesn’t provide enough consistent sunlight for grid-scale solar to replace dispatchable power sources.

The Backup Burden

Because solar output fluctuates with the weather and time of day, it cannot operate alone. Every megawatt of solar capacity must be backed by another megawatt of flexible generation — usually gas-fired turbines — that can ramp up instantly when the sun disappears.My screenshots show gas rising and falling hour by hour to balance solar’s dropouts. This “shadow system” burns fuel inefficiently, increases wear on turbines, and locks consumers into paying for two overlapping infrastructures: one intermittent, one reliable.Environmental campaigners often point to battery storage as the answer. But again, the data expose the scale problem.

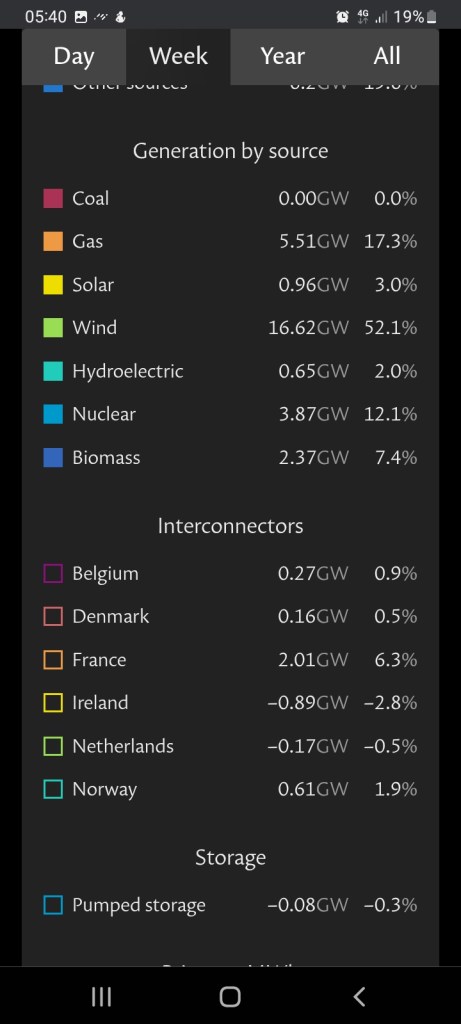

Screenshot 4 – storage summary 0.4 %

My screenshots show total pumped and battery storage supplying just 0.09 GW — 0.4 % of generation. That’s roughly enough to power the grid for less than two minutes. Even if all proposed Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) projects were built, they would store only a few hours of power -nowhere near the days or weeks required to cover a dark winter spell.

The Cost Illusion

Politicians and solar developers frequently claim that solar is now “the cheapest form of electricity.” But the price quoted – usually around £40 per MWh – ignores the costs of backup, storage, and grid reinforcement.

My screenshots show wholesale prices in the range of £62.79 – £87.62 per MWh, even with high renewable penetration. Consumers have not seen cheaper bills; instead, standing charges and system-balancing costs have soared.When full system costs are included – standby gas plants, batteries, inverters, and transmission upgrades – the real cost of solar energy often exceeds £100 – £120 per MWh. And these figures do not include the environmental and social costs of converting green fields and farmland into industrial energy sites.

The Land Use and Environmental Contradiction

The UK has already approved or proposed more than 150 large-scale solar farms, many on Grade 2 or Grade 3 agricultural land. Each gigawatt of solar requires around 5,000 acres, and much of this land is permanently removed from food production.Contrary to the “green” image, solar farms damage soil structure, increase runoff and flooding risk, and reduce local biodiversity by shading out ground flora. My screenshots, showing solar’s minimal contribution at national level, highlight how irrational this trade-off is – sacrificing food security for a technology that delivers only a few percent of total generation.

The Economic Trap of Intermittency

Screenshot 5 – interconnector data

Another revealing pattern in my screenshots is the behaviour of interconnectors.

On days of weak solar output, the UK imports power from France and Norway – up to 11 % of demand at times – while exporting excess wind power when prices turn negative.This cross-border shuffling doesn’t make the system greener; it makes it more fragile. France’s baseload is nuclear, while Norway’s is hydro. In effect, the UK is leaning on its neighbours’ dispatchable capacity to mask domestic intermittency. That dependence adds to costs and undermines energy sovereignty.

The Engineering Consensus

When the Climate Change Committee and successive governments pushed solar as a pillar of Net Zero, many engineers warned that the numbers would never add up. Britain’s energy system needs high-inertia, dispatchable, synchronous generation – sources that maintain grid stability and deliver power when required.

Solar provides none of these qualities. It produces DC current that must be inverted, destabilises frequency, and disappears at the very moment evening demand peaks.

To keep the lights on, National Grid ESO must constantly call on gas stations, hydro, and imports.

As the late Professor Sir David MacKay wrote.

in Sustainable Energy – Without the Hot Air:“If everyone does only a little, we’ll achieve only a little. To make a difference, we need a plan that adds up.”

Seventeen years after the 2008 Climate Change Act, the solar plan still doesn’t add up.

The Better Alternatives

Instead of carpeting the countryside with panels and batteries, Britain could invest in technologies that genuinely align with our geography and industrial base:

Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) – reliable, domestic nuclear power with a small footprint.

Rooftop and building-integrated solar film (such as the Power Roll technology developed in the North-East) generation where it’s used, without new transmission lines.

Upgraded gas and hydro plants providing synchronous inertia and flexible generation.

Modern grid infrastructure built around demand, not ideology.These options support energy sovereignty, create skilled jobs, and deliver stable output without disfiguring rural landscapes.

Conclusion:

What My Screenshots Prove

Across all the screenshots, one fact remains constant: solar’s contribution is marginal and unreliable. Whether viewed hourly, weekly, or across the year, its share fluctuates between 0 % and 7 %, disappearing entirely at night and in winter.

Meanwhile, the technologies that actually keep Britain powered – gas, wind, nuclear, and biomass – must shoulder the entire system load while absorbing the distortions caused by intermittent generation.

The government, the CCC, and environmental campaigners have mistaken visibility for viability.

Solar farms look green in photographs, but the numbers on the grid tell a different story.

My screenshots show, beyond any argument, that Britain’s energy system is still overwhelmingly dependent on dispatchable sources. Solar is a supplement, not a solution – a technology that vanishes when it’s most needed and drives up the cost of everything built to back it up.

It was, as engineers warned from the start, a dream that ignored physics. The time has come to replace ideology with engineering and rebuild a power system that works when the sun doesn’t shine.

By Shane Oxer — Campaigner for fairer and affordable energy

Leave a comment