How Wind and Solar Are Destroying Britain’s Landscapes, Forcing a £300 Billion Grid Rebuild, and Still Leaving Us Powerless in Winter

By Shane Oxer Campaigner for fairer and affordable energy

Britain is being physically reshaped before our eyes. From the Scottish Highlands down through Yorkshire, across Lincolnshire, and along the Kent coast, a web of gigantic pylons, high-voltage corridors, and industrial substations is spreading across the landscape. This is not a national renewal. It is not an upgrade made in the name of energy security. It is a desperate, chaotic, astronomically expensive attempt to make unreliable wind and solar behave like the constant power sources they can never be.

Look at the infrastructure I’ve shared:

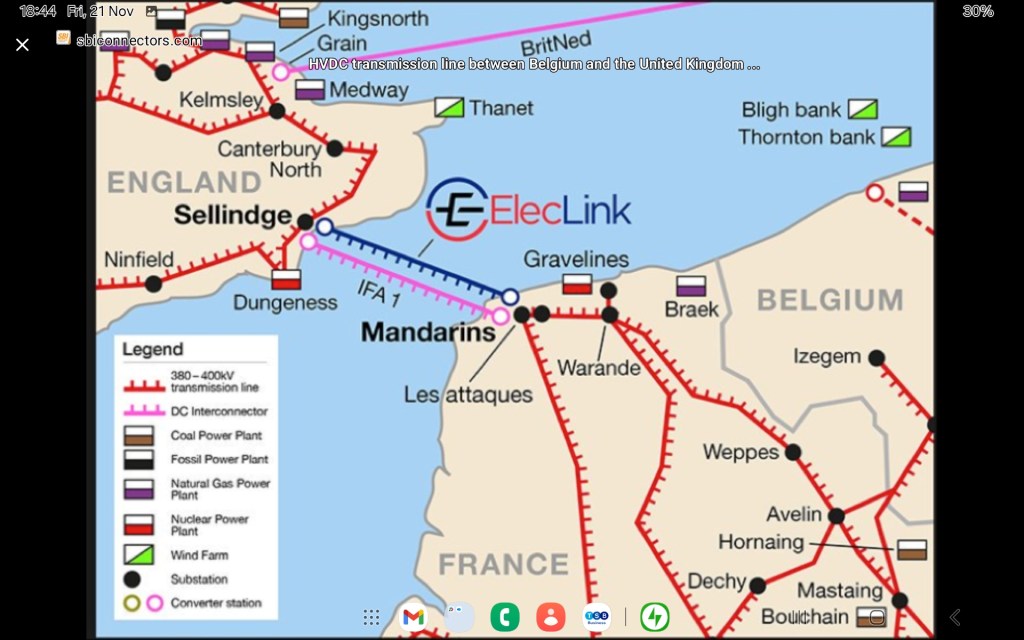

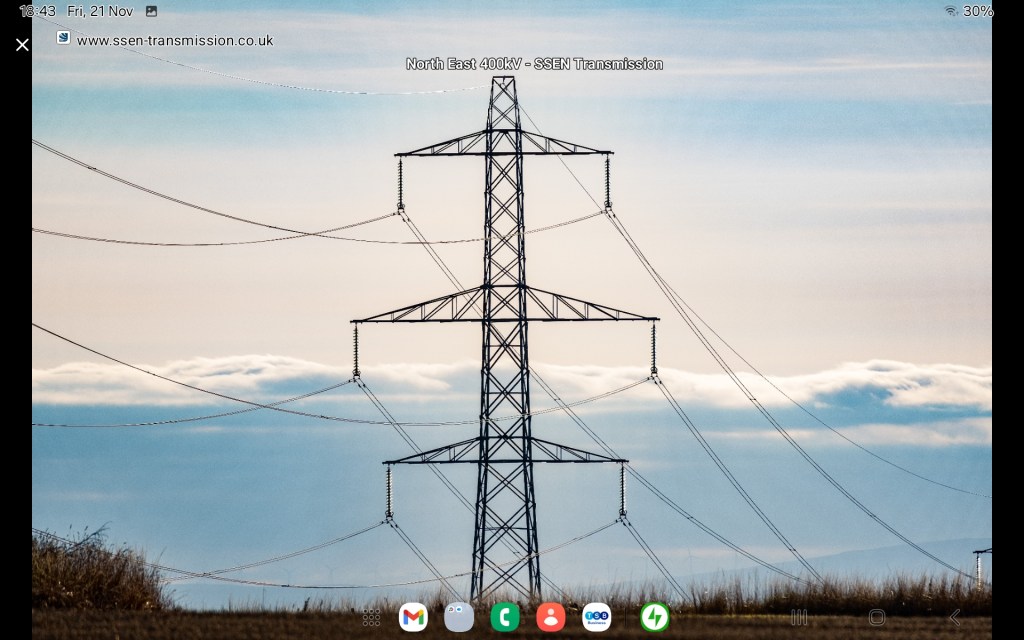

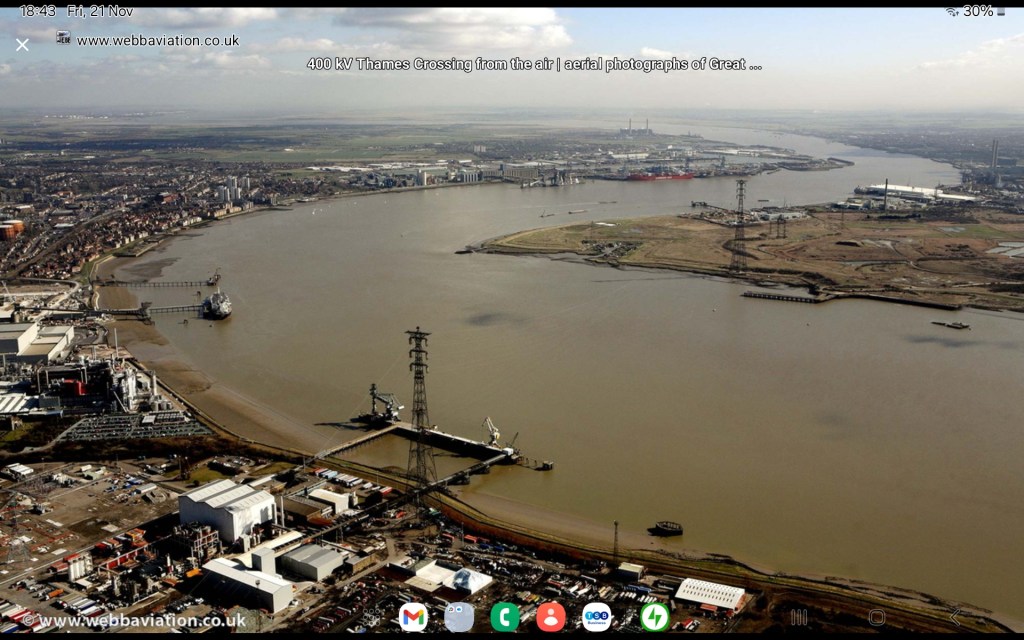

The map around Sellindge and Dungeness shows the cluttered tangle of interconnectors – blue for the IFA line, purple for the ElecLink cable, that now snake under the English Channel. They exist because Britain’s wind fleet repeatedly collapses in cold, still winter periods, forcing us to pull in foreign electricity. The image of the huge SSEN 400 kV substation, with its forest of metallic switchgear standing under a grey, oppressive sky, makes clear just how industrial this “green revolution” truly is. Then there is the map of Grimsby West to Walpole, the new east-coast corridor National Grid is carving through some of the country’s most fertile farmland. The pylon photograph, tall, stark, dominating the horizon,shows what this system looks like when it lands in a field near you. And the Thames Crossing aerial view, with giant towers straddling the river, tells us plainly: nowhere is safe from this transformation.

All of this is happening because wind and solar cannot provide the reliable, continuous electricity that a modern country requires. Britain’s demand does not fluctuate with the weather. We need stable power every hour of every day. Yet solar produces almost nothing in winter, especially from November to February, when generation drops to as little as 2–8% of its nameplate capacity.[1] Wind, meanwhile, is increasingly recognised as a fair-weather friend. During winter “blocking highs” those cold, motionless pressure systems known as Dunkelflaute. Wind generation falls to barely 5% of its installed capacity.[2] It can persist for days or even weeks, precisely when heat, light, and power demand is at its highest.

Because renewables fail during the very season Britain most needs power, the grid must be redesigned around their weaknesses. This is the real reason National Grid Electricity System Operator (ESO) now estimates that at least £58 billion of new transmission infrastructure is needed.[3] But this figure is misleadingly clean. Once you include inflation, HVDC expansions like Eastern Green Link 1 and 2, the vast number of new substations, undergrounding in protected areas, and the reinforcement of local distribution networks, the true cost is likely in excess of £300 billion. That is more than Britain spent building its entire motorway system after the Second World War. And it is happening not to improve the grid, but to prop up technologies that cannot replace the coal, gas, and nuclear power stations they have politically displaced.

The environmental cost is even harder to ignore. In the Highlands, 400 kV lines are now being driven from Spittal to Loch Buidhe, and from Beauly to Peterhead, through mountain landscapes that have barely been touched for centuries. The shiny steel frameworks in the SSEN image are only the beginning. In Lincolnshire, the Grimsby West to Walpole project will march hundreds of pylons through open countryside and farmland, alongside enormous substations that will forever alter rural skylines. Yorkshire’s greenbelt is being rearranged to accommodate Yorkshire GREEN, a set of substations and overhead lines that no local community ever asked for. And the Thames Crossing shows how even Britain’s estuaries and heritage coastlines are becoming industrial corridors.

It is important to understand that every one of these pylons, substations, converter halls, and cable routes exists because wind and solar cannot be relied upon. Modern gas power stations take hours to start; nuclear takes days. So when the wind disappears without warning, National Grid must decide instantly whether to import power, fire up gas at huge cost, or begin load-shedding. Britain consumes around 850 GWh of electricity per day, yet the entire grid-scale battery fleet stores less than one gigawatt-hour. In other words, the grand “battery revolution” can keep Britain going for about three minutes. It is mathematically impossible for batteries to bridge the gap left by week-long winter wind droughts.

This truth is now leaking into political language. Even Ed Miliband, long-time champion of renewables, has quietly admitted that Britain will need new gas-fired generation to guarantee winter security.[4] The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) has confirmed repeatedly that thermal generation must remain on the system for the foreseeable future.[5] And with the explosion of AI and data centre demand, the same ministers who once claimed “renewables alone can power Britain” now insist that we need new nuclear fibres of baseload to keep the digital economy online.[6]

Meanwhile, your bills continue to rise. Standing charges have increased by more than 500% across some regions in the last decade.[7] Constraint payments — money given to wind farms when the grid can’t handle their output — now cost consumers hundreds of millions of pounds per year. Offshore wind farms must be connected to shore through expensive HVDC cables and converter stations that cost billions. New substations, like the ones shown in your images, require super-grid transformers, shunt reactors, STATCOMs, and control systems that run into hundreds of millions per site. All of this is funded through your energy bills, your taxes, and your local environment.

And the worst part? After all the billions spent, after the pylons erected through rural villages, after the substations that swallow fields, after the interconnectors laid across the seabed — we still end up relying on gas and nuclear every winter. In other words, Britain is industrialising its countryside, destabilising its energy system, and loading costs onto households for technologies that cannot stand on their own.

There was and still is, a better path. Modern gas plants located close to demand could reduce the need for long-distance transmission. Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), such as those developed by Rolls-Royce, can be placed on existing grid nodes at old coal and nuclear sites, removing the need for new pylons entirely. Rooftop solar technologies (such as Power Roll’s thin-film systems) create local generation without consuming farmland or requiring new high-voltage infrastructure. A rational, reliability-first strategy would protect our landscapes, stabilise the grid, cut costs, and ensure energy security. But ideology, not engineering, has guided Britain’s energy transition — and the consequences are now unavoidable.

Britain is spending over £300 billion on a grid designed around failure. We are tearing up mountainsides, farmland, and greenbelt to chase energy that disappears every winter. We are undermining our own security of supply in the name of a political project. And worst of all, the people funding this catastrophe — ordinary families, farmers, and communities — were never given the facts.

Wind and solar were sold as clean and cheap. The reality is dirty, expensive, and destructive. The images you provided do not show a green future; they show a country being quietly sacrificed.It is time the public saw the truth without filters or political spin.

Footnotes

[1] National Grid ESO Solar Seasonal Generation Statistics, 2015–2023

[2] Met Office and ESO Reports on Extended Dunkelflaute Events

[3] National Grid ESO, Beyond 2030 Investment Programme, 2023–2024

[4] The Telegraph, July 2025: “Miliband to unleash new gas plants to back up patchy wind and solar”

[5] DESNZ Winter Security Briefings, 2023–2025

[6] UK Government AI Infrastructure Strategy, 2025[7] Ofgem Standing Charge Trends, Regional Data 2014–2024

Leave a comment