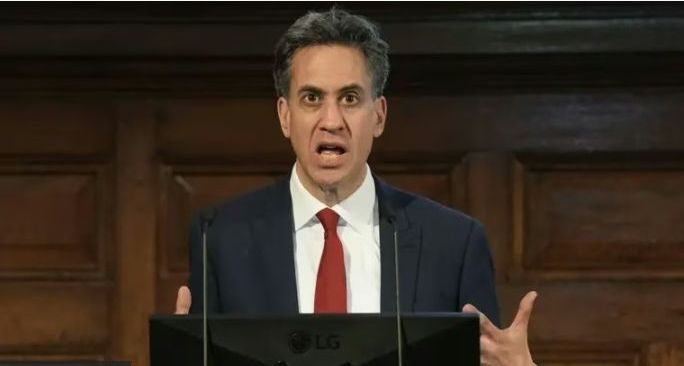

COP30 has now drawn to a close in Belém, and for the first time in years the climate summit felt less like a stage-managed ritual and more like a system hitting its limits. The language was familiar, the slogans unchanged, but the cracks in the Net Zero narrative were impossible to hide. What emerged was not a reaffirmation of global consensus but a quiet, unmistakable acknowledgement that the world can no longer pretend the old promises are deliverable. And that brings us to the unavoidable question facing Ed Miliband: will he finally confront reality, or will he cling to an ideology

The official COP30 text repeated what has become a kind of annual incantation: that the global food system must be transformed to absorb three billion tonnes of carbon dioxide each year; that humanity must find entirely new ways to remove five billion tonnes more from the atmosphere; and that forests, wetlands and ocean ecosystems must somehow be restored at a scale never before attempted.[1][2][3] These assertions are not new—they are the backbone of the Net Zero worldview—but what changed this year was the international response. Behind the closed doors of negotiations, countries that have previously nodded politely at these numbers openly questioned their feasibility. The idea that the world can re-engineer agriculture, deploy unproven industrial carbon capture technologies at planetary scale, and rewild millions of hectares simultaneously is no longer seen as visionary. It is increasingly viewed as absurd.

The scientific panels can repeat these targets, but the underlying reality is unchanged: global food systems cannot sacrifice yield to absorb additional carbon without risking food security.[4] Direct Air Capture remains a niche technology consuming vast amounts of energy per tonne removed.[5] And nature-based sequestration is far too land-intensive to shoulder the burden policymakers want to dump on it.[6] COP30 did not correct these contradictions, but it did expose them. The world is waking up to the fact that the climate agenda has been held together by assumptions that simply do not survive contact with physics and economics.

The summit also revealed the hardening conflict between Europe’s ideological climate policy and the economic realities facing the rest of the world. Nowhere was this clearer than in the dispute over the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. European officials insisted that the border tax has nothing to do with protectionism and everything to do with “fairness” and “emissions integrity,” yet every trading partner watching understood it for what it is: an attempt to shield European industries from cheaper imports made competitive precisely because they are not crippled by EU climate rules.[7] The fact that the issue had to be postponed to “future dialogue” was not a diplomatic victory. It was a sign that the old climate narrative no longer commands automatic deference. The global south and major emerging economies are no longer willing to absorb economic punishment so that Europe can uphold its green self-image.

While Europe and the United States wrestled with ideological positions, China demonstrated once again that it understands the material realities of energy far better than its competitors. Throughout COP30, China maintained a low political profile, avoided the theatrics of climate virtue signalling, and instead focused on doing what actually matters: securing markets for its solar technology and expanding its industrial leverage. With more than 80% control over global solar supply chains, China does not need to dominate the political conversation at COP. It dominates the economics of the transition itself.[8] This simple fact—more than any communiqué or pledge—shows how naïve Western policymakers have been. While they legislate targets, China builds the factories that will profit from them.

The fossil fuel negotiations told a similar story. Saudi Arabia, Russia, and other major producers did not need to stage a diplomatic battle. They simply stated that they would not agree to language committing them to an unrealistic fossil fuel phase-out, and the entire roadmap collapsed. The final agreement retreated to the familiar diplomatic safe zone of “ongoing dialogue,” which in UN terms is code for “there was no agreement at all.” This was not obstructionism; it was an assertion of reality. These nations know that the modern world runs on dense, reliable energy, and no amount of aspirational text can replace oil and gas before viable alternatives exist. COP30 brought that truth from the margins to the centre of the conversation.

This global shift lands squarely on Ed Miliband’s desk. The world is moving away from the ideological rigidity he helped to embed in the UK through the 2008 Climate Change Act.[9] The Climate Change Committee he empowered has since evolved into a quasi-legislative body that dictates energy policy without democratic accountability.[10] And yet Miliband refuses to acknowledge that the Net Zero project is collapsing under its own weight. To face reality now would require him to admit that Britain has spent hundreds of billions of pounds on technologies that cannot scale, that energy bills have soared because the system was redesigned around intermittency, and that China—not the UK—now dictates the economics of the global energy transition.[11][12]

So Miliband faces a stark choice. He can cling to the ideology he built his political life around, insisting that more targets, more restrictions, and more subsidies will somehow deliver the energy utopia that has failed to materialise for fifteen years. Or he can accept what COP30 has made undeniable: the world is stepping back from the unrealistic dogma of Net Zero and acknowledging that energy security, affordability, and national resilience must come first. Every signal suggests he will choose the former. It is easier to cling to an identity than to admit a mistake of this magnitude.

COP30 did not mark a triumph of pragmatism, but it did mark the end of something: the illusion that global climate policy can be sustained by wishful thinking. The summit exposed the limits of carbon removal, the failure of rapid fossil fuel phase-out language, the protectionist heart of European policy, and the industrial dominance of China. It revealed a world quietly stepping away from the fantasy and rediscovering the need for energy realism. The ideology has not been defeated—it has simply been overtaken by reality.

For Britain, the message is clear. Our energy future cannot be built on targets that ignore engineering limits or on policies that punish industry while empowering competitors overseas. COP30 has shown that the old narrative is collapsing, and the only question now is whether our political leaders have the courage to follow the world back to reality. Ed Miliband’s response will tell us everything we need to know about whether Britain chooses survival—or continues down the path of Net Zero fantasy.

Footnote.

1. COP30 Draft Text, Food System Carbon Removal Ambition.

2. Ibid., Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) Targets.

3. COP30 Nature-Based Solutions Working Group Outcome Summary.

4. FAO Land Use and Food Security Assessment (2024).

5. International Energy Agency, Direct Air Capture Status Report (2023).

6. IPBES Land Use and Biodiversity Report (2022).

7. European Commission, CBAM Legislative Rationale (2023–25).

8. International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Solar PV Supply Chain Report (2024).

9. House of Lords Industry Report on the Climate Change Act, 2020 Review.

10. Public Accounts Committee, Oversight of the Climate Change Committee (2022).

11. Treasury Net Zero Review, Part II (2023).12. OECD Industrial Strategy Comparative Analysis (2024).

Shane Oxer. Campaigner for fairer and affordable energy

Leave a comment