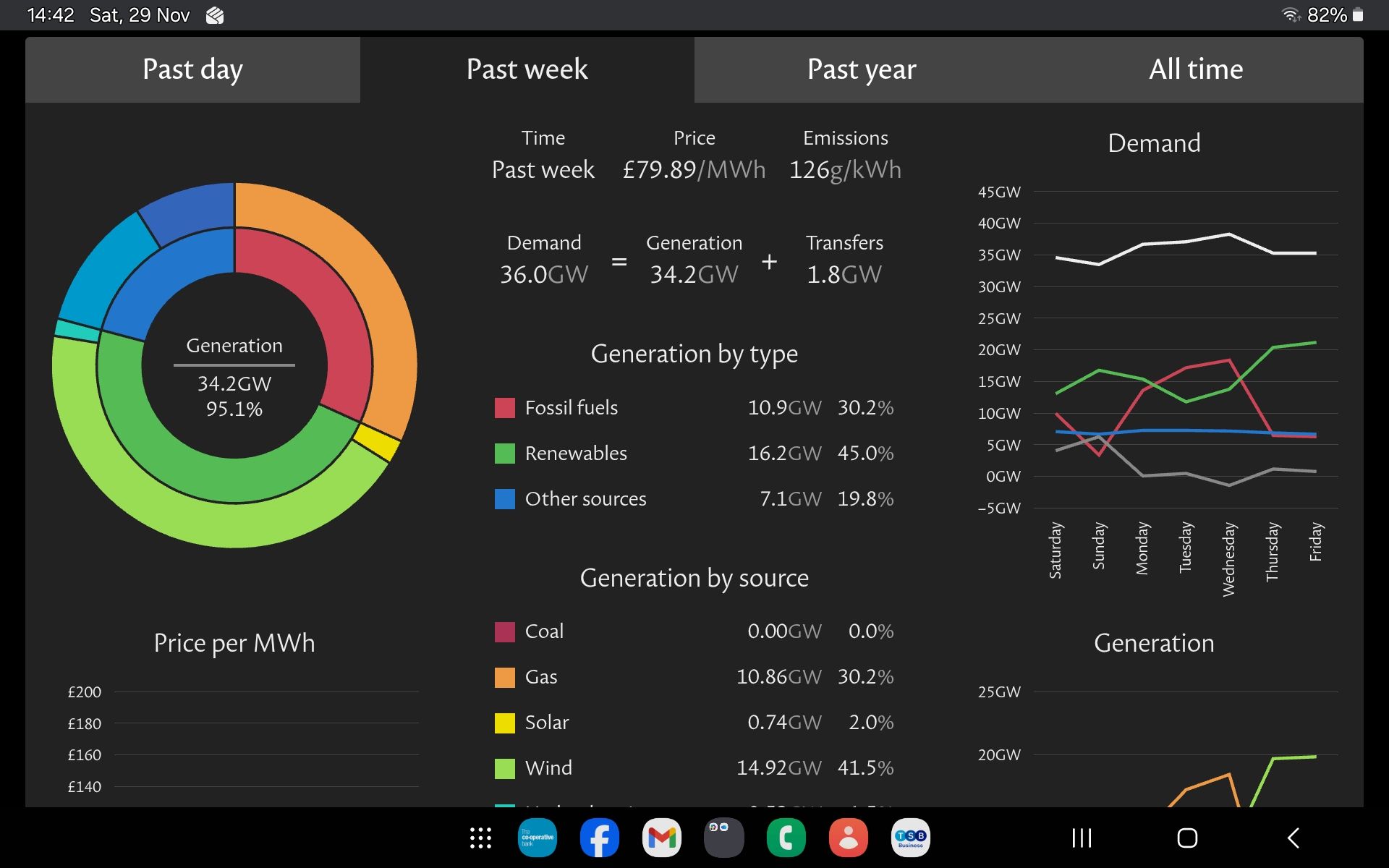

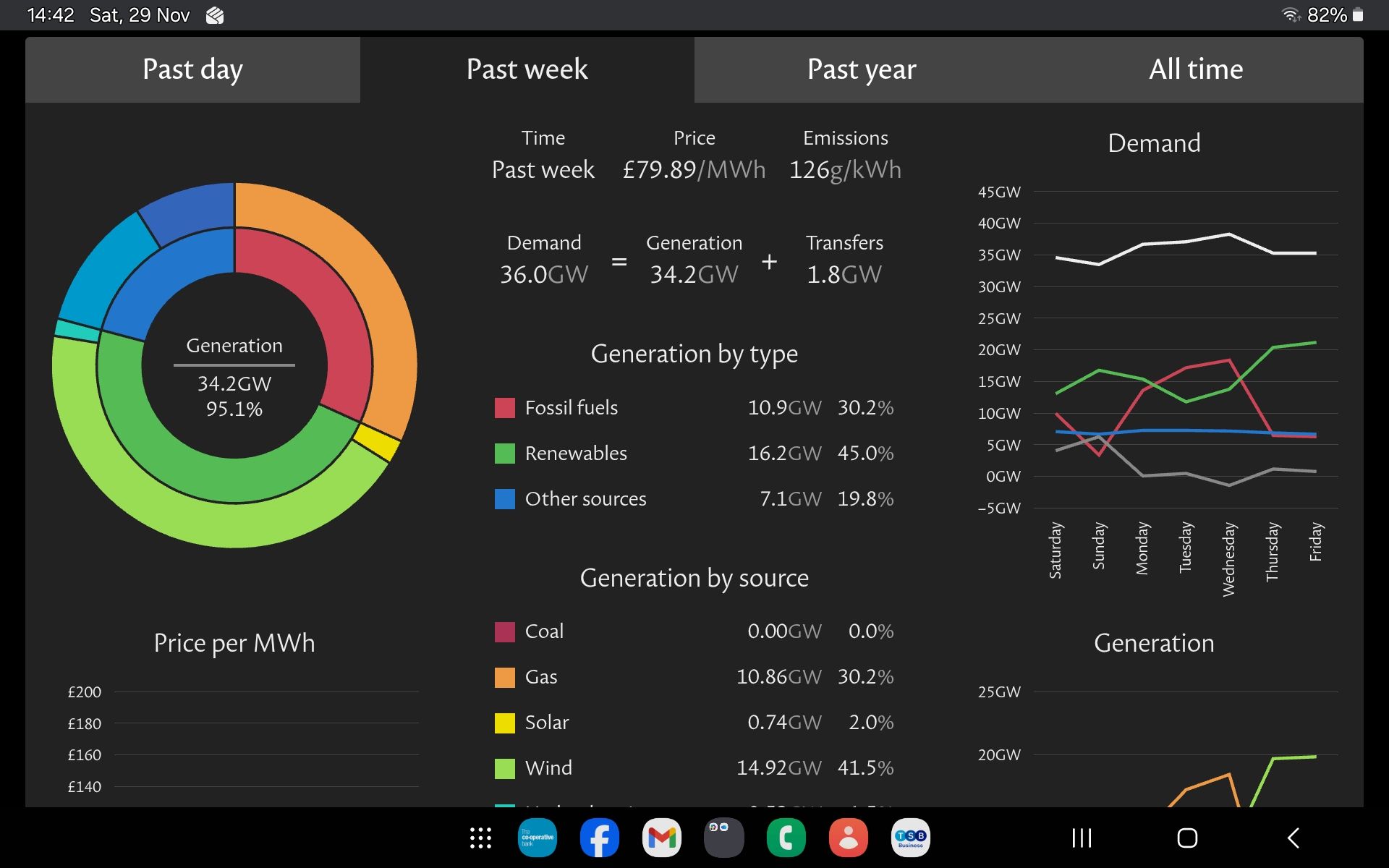

The latest grid data tells a story that no amount of political messaging or PR spin can hide. Despite more than twenty gigawatts of installed solar capacity across the UK, actual solar output in winter collapses to a fraction of that headline figure. The screenshot above shows solar contributing just 0.74 GW, barely 2% of national demand, at a time when the country requires over 36 GW of electricity.¹ This is the clearest possible demonstration that installed capacity means nothing if the generation is not available when people need it most.

Wind, by contrast, performs relatively strongly in this snapshot at 14.92 GW, or around 41.5% of total generation.² However, this does not resolve the fundamental problem. Wind generation varies dramatically from hour to hour and day to day. It cannot be relied upon as the backbone of a modern electricity system that must remain stable under all weather conditions. When wind output falls—as it routinely does—there is only one technology that consistently steps in to fill the gap: gas.

In the same dataset, gas generation stands at 10.86 GW, accounting for just over 30% of total supply.³ This is not an accident or a temporary quirk of the system. Gas-fired generation is dispatchable: it can be increased or decreased instantly to stabilise the grid as renewable output fluctuates. Every time the wind drops or solar disappears at sunset, gas ramps up to prevent blackouts. The system remains secure not because of renewables, but because of the fossil-fuelled resilience embedded within it.

This exposes the core engineering truth that policymakers continue to ignore: electricity demand is constant, but renewable output is not. Demand does not fall when the sun goes down. It does not soften when the wind drops. People still need heating, lighting, hospitals, transport, refrigeration, and the entire architecture of modern life. Reliability is not optional; it is the foundation of civilised society.

Yet successive governments have pursued a strategy built on the assumption that intermittent renewables could replace dependable baseload power. The evidence now shows that this experiment has failed. Winter solar output remains negligible, wind output remains unpredictable, and grid balancing costs are rising as the system becomes ever more dependent on rapid-response gas plants to cover renewable volatility.⁴

The implications are profound. When renewables fail to deliver, gas generators must operate inefficiently in stop-start mode, increasing system costs. Backup infrastructure must remain on standby even when not generating. Batteries cannot compensate for multi-day shortfalls, and the UK has no viable seasonal storage technology. Consumers pay the price through higher bills, and the countryside pays the price through relentless expansion of solar and wind farms that do little to keep the lights on in winter.

If Britain wants lower bills, a secure grid, and an energy system that functions year-round, then it requires constant, reliable, sovereign generation. That means nuclear—particularly domestically designed SMRs—practical gas capacity, hydro, and rooftop microgeneration technologies that do not destroy farmland. It does not mean covering productive fields with intermittent solar farms or relying on wind turbines that collapse to single-digit output levels during winter anticyclones.

The screenshot shown in this blog is not an anomaly. It is the reality of the UK grid every winter. It is the reality that policymakers refuse to confront. And it is the reality that proves beyond doubt that Britain cannot rely on intermittent renewables to power a modern industrial economy.

Footnotes

1. National Grid ESO data (past week view), showing 0.74 GW solar output against 36 GW demand.

2. Ibid., wind generation recorded at 14.92 GW.

3. Ibid., gas generation recorded at 10.86 GW.

4. See system-balancing cost trends and ESO Winter Outlook reports indicating rising costs associated with renewable intermittency.

Shane Oxer Campaigner for fairer and affordable energy

Leave a comment