For years, critics of the UK’s Net Zero strategy were dismissed as pessimists, naysayers, or politically motivated. This week, that narrative finally collapsed. Not because of an activist campaign or opposition speech, but because the engineering supply chain itself has broken cover.

When the world’s leading manufacturer of high-voltage transformers publicly warns that Britain may not be able to build its electricity grid fast enough to meet Net Zero targets, the argument is over. This is no longer about belief, ambition, or political will. It is about physical limits.

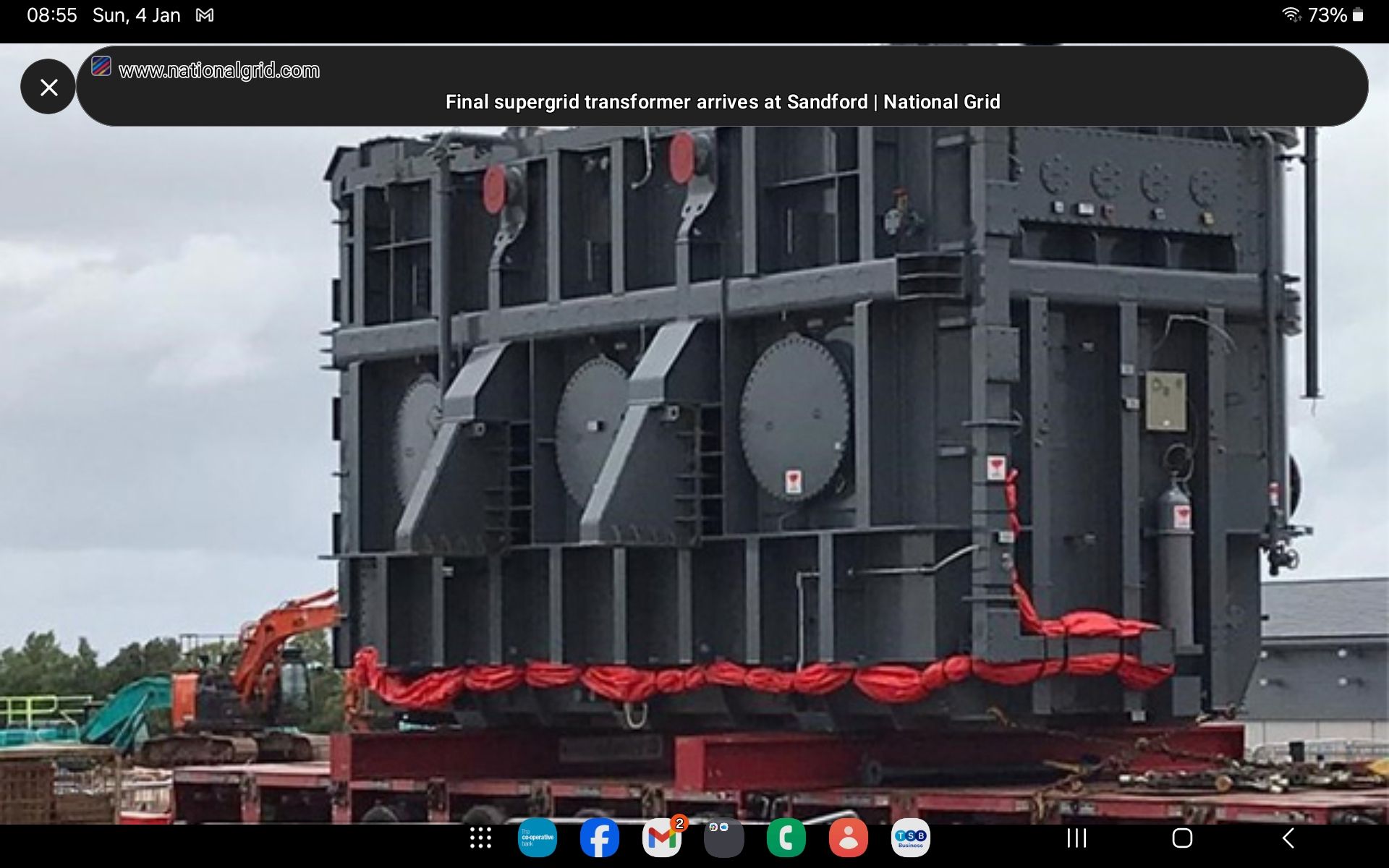

The warning is stark: the UK’s electricity system is built on ageing infrastructure, much of it 50–60 years old, and the equipment required to replace and expand it simply cannot be manufactured or delivered at the speed government policy now demands. Transformer lead times have exploded from months to years. Prices have surged. Skilled labour is scarce. Raw materials are constrained. And Britain is not competing in a vacuum — it is bidding against the rest of Europe, the US, and now the global AI boom for the same finite industrial capacity.

This matters because transformers are not optional extras. They are the backbone of the grid. Every wind farm, solar array, nuclear plant, data centre, rail line, heat pump and EV charger depends on them. Without enough transformers, generation capacity is meaningless. Power cannot move, voltage cannot be stabilised, and systems cannot be made resilient.

The article quietly exposes the fatal flaw in current policy: the decarbonisation deadline was politically accelerated from 2035 to 2030 without any corresponding acceleration in physics, manufacturing, skills, or finance. Factories cannot be built by press release. Supply chains cannot be willed into existence. And heavy electrical equipment does not obey election cycles.

The consequences are already visible. Britain is approving tens of billions of pounds of grid investment that will be added directly to household bills — yet the equipment itself will largely be manufactured abroad. Thousands of skilled jobs are being created in Poland, Sweden, Germany, Spain and Italy to serve UK demand, while Britain imports the hardware and exports the opportunity. This is not a green industrial revolution; it is de-industrialisation with a climate badge.

Even more damaging is the collision with reality brought by artificial intelligence. Data centres demand vast amounts of stable, uninterrupted power , the very opposite of what intermittent, inverter-heavy systems naturally provide. Manufacturers now estimate that hundreds of additional giant transformers will be required across Europe by 2030 just to power AI, competing directly with Net Zero grid upgrades for the same constrained equipment.

This exposes the deeper contradiction at the heart of Net Zero policy: it assumes an energy system that is simultaneously cheaper, greener, more reliable, more decentralised, more digital and yet somehow built faster, with fewer materials, fewer workers, and less time than any comparable infrastructure project in history. That assumption has now been publicly disproven by the people who actually build the system.

The Heathrow blackout, caused by a 60-year-old transformer, was not a freak accident. It was a warning shot. Super-grid transformers are single-point failures with multi-year replacement timelines. As the system becomes more complex and more stretched, these risks multiply. Decarbonisation, far from simplifying the grid, adds layers of transformation, conversion, and vulnerability.

What makes this moment so significant is that the Government response does not challenge the facts. There is no denial of the shortages, no rebuttal of the lead times, no claim that targets remain deliverable. Instead, there is only vague language about “working closely” with industry — a tacit acknowledgement that the plan is running ahead of the tools required to deliver it.

This is why so many communities are now being told that solar farms, wind projects and battery sites will be approved long before their grid connections exist. It is why “zombie projects” are stacking up in connection queues stretching into the 2030s. And it is why consumers are paying more each year for a system that is becoming less secure, not more.

Net Zero has not failed because the country lacked ambition. It is failing because ambition replaced engineering, targets replaced planning, and ideology replaced deliverability. The supply chain has now said out loud what campaigners, engineers and local communities have been warning for years: you cannot build a power system on deadlines that ignore reality.

The most telling line in the entire article is this: manufacturers will not invest in the UK without long-term policy stability beyond 2030. In other words, even the companies meant to deliver Net Zero do not believe the current strategy is coherent or durable.

That is not a warning about climate change.It is a warning about governance.

And it confirms, beyond doubt, that the grid crisis now unfolding was not unforeseen , it was designed in by policy.

Shane Oxer . Campaigner for fairer and affordable energy

Leave a comment