By Shane Oxer. Campaigner for fairer and affordable energy

Richard Eden’s diary column wasn’t meant to be an environmental dispatch. It was a society story: titled landowners, old friends of princes, and a “500-strong rebellion” on a great estate.

But he got one thing exactly right , and it changes the entire frame.

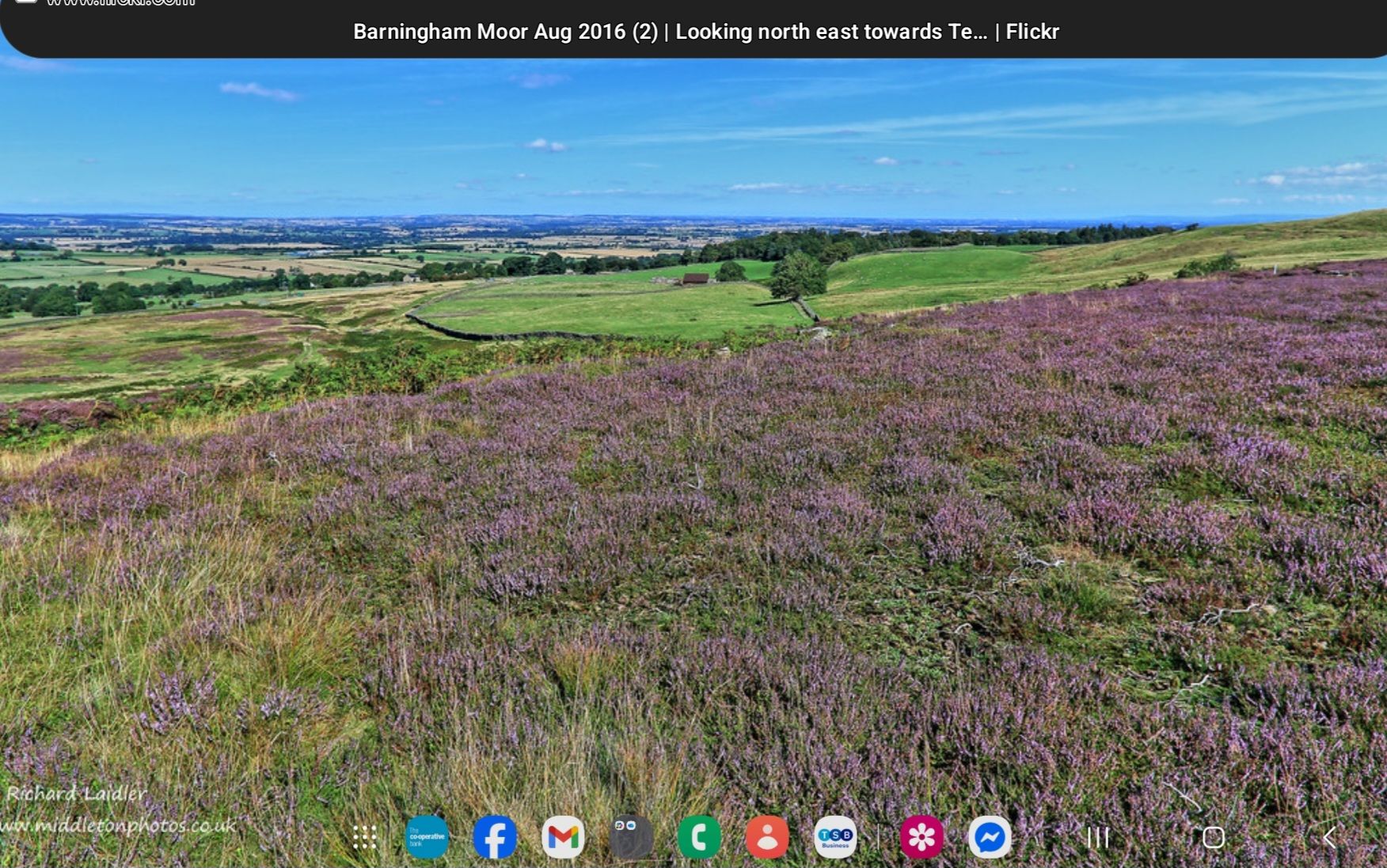

He described Barningham as “a breathtaking expanse of unsullied moorland.”

That phrase is dynamite.

Because the proposed Hope Moor Wind Farm by Fred. Olsen Renewables sits on that very ground: high, open Pennine moor in the setting of the North Pennines and the Yorkshire Dales National Park. Turbines approaching 200 metres would be planted across it under a Section 35 direction of the Planning Act 2008, meaning the decision is lifted out of local hands and into Whitehall.

So the real question Eden accidentally poses is this:

If this is “unsullied moorland”, why does Whitehall think it’s suitable for 200-metre industrial structures?

This has happened here before

A generation ago, Mary Elizabeth Mann fought almost the same battle on Barningham High Moor , the same landscape, the same arguments, the same policy pressure. She learned the planning system, documented every step, and helped defeat a wind farm proposal that went as far as the High Court.Her case became a quiet landmark among countryside campaigners because it exposed an uncomfortable truth: when national policy bears down, the system bends toward delivery, not judgment.

Hope Moor feels like history repeating , only taller, cruder, and centralised through NSIP powers.

Not a society story. A countryside test.

This isn’t about personalities or leases. It’s a stress test of what “protected landscape setting” means in practice when targets bite.

On high moor, 200 m turbines become region-defining structures.Upland peat and hydrology are not cosmetic concerns; they regulate water and store carbon.The site sits roughly 25–30 km from Teesside International Airport; obstacle fields at this height on elevated ground raise legitimate aviation safeguarding questions about radar, procedures, and future airspace options.And all of it lands in a grid already paying heavily for curtailment where generation outpaces network capacity.None of that fits the caricature of a quaint local spat.

The lesson Whitehall didn’t learn

Mary Mann’s fight showed what happens when policy becomes dogma and landscapes become collateral. Instead of fixing that bias, the state has centralised it.

The question quietly shifts from “is this right for here?” to “how do we make this fit policy?”

Eden’s phrase , unsullied moorland , brings us back to first principles.

If this ground is acceptable for industrialisation, then the map of “too sensitive to touch” has shrunk not because the land changed, but because the policy did.

That’s the story,And it’s much bigger than a few royals wishing to make ends meet.

Eden Was Right About One Thing: This Is Unsullied Moorland

Leave a comment